![Absent Histories: A Case of Hyderabadi Siddis and Hadramis[1]](https://zariya.online/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Screenshot_20210115-213023_3.jpg)

Absent Histories: A Case of Hyderabadi Siddis and Hadramis[1]

Hari Masjid, Safed Khane

Usme Baithe Siddi Diwane

~ A Hyderabadi Riddle[2]

Hyderabad has had a Siddi, or African, presence since the time of the Qutab Shahi dynasty, which had Habshi soldiers (Habsh, in Arabic or Urdu, loosely refers to the region now called Ethiopia and Eritrea) in their army and Habshi guards guarding their bastions – including a contingent of Habshi female guards called gardan were also part of the Qutab Shahi security. Even today, these histories can be witnessed in artefacts paying homage to translocal movement of people around the Indian Ocean, for example, the Habshi kamaan (African Arch) in the Golconda Fort where Habshi soldiers used to be stationed or in the name of neighbourhoods like Siddipet or African market, Habshi Guda or African village and African Cavalry Guards (A C Guards).

Further, Africans slave elites, including African eunuchs, have been documented in paintings from the Qutub Shahi period (See Campbell, “Slave Trade,” 19; El Edroos and Naik, Hyderabad of Seven Loaves, 13–31; and Harris, The African Presence in Asia, 114). Whereas, the institution of slavery existed across the Islamicate world, it was not restricted by the identity – race, gender, caste etc. – of the person. Many slaves in the Islamicate world went on to rise to positions of power as rulers, generals and administrators, for example, Malik Ambar of Ahmadnagar, the Mamluks of Egypt or the Slave Dynasty in South Asia. The important role of African origin slave elites is well documented under the Islamic rulers of Deccan.

The Asaf Jahi Princely State of Hyderabad, a successor of the Qutab Shahi State, similarly boasted of a large African population by the beginning of the 19th century. The State of Hyderabad under the Asaf Jahi was answerable to British colonial authorities and had trained its army under British control for internal security only. Siddis were employed as irregular soldiers, guards, riders, stable keepers and domestic help, in addition to working in Nizam’s army, police forces and exclusively forming the Nizam’s Royal Body Guards, the Siddi Risala. The Siddi Risala had two components, the Prince’s Body-Guards and the Nizam’s Body Guards. The descendants of the Siddi Risala are still living in Hyderabad.

Today, Siddis in Hyderabad are concentrated in a neighbourhood called African Cavalry Guards (A C Guards) named as such after the Siddi Risala. A C Guards were royal stables that were converted into housing by Asaf Jah IV in the 1840s to provide housing for his Siddi Risala. Thus, A C Guards link many Siddis to their past in Hyderabad.

Siddi migration, especially in the later Asaf Jahi period, is linked to the movement of Arab Hadramis. Movement of these Afro-Arab communities, like the Siddis, in the Indian Ocean is embedded in a complex web of multiple journeys and middle passages. During the anti-abolitionist movement, these were characterised by different regimes of migration, for example, Arab Hadramis would often disguise Africans as their wives or relatives to get through the customs authorities on the Port of Bombay, which was under the British colonial jurisdiction.

Similarly, the elites going on the Hajj pilgrimage would return with African slaves purchased in the Arabian Gulf, posing them as their relatives. In Hyderabad, both Siddis and Hadramis identify themselves as Chaush, a Turkish word for ‘soldier’. The Chaush as a group are distinct because of their African/Arab/Afro-Arab lineage and because of theological differences with the majority Hanafi Muslim community – both the Siddi and Hadrami community follow the Shafai’i maddhab (both are schools of thought within the the Islamic Fiqh or jurisprudence).

Both Siddis and the Hadramis are ghettoised in the ‘older part of the city’ and the ‘Old City’ in Hyderabad, respectively, much like other Deccani Muslims. These communities are living testimonies to a past that is distinct. Both communities worked for the Nizam’s State, with Hadramis occupying positions from the top ranks in Hyderabad State Forces to irregular soldiers. Conversely, the African Cavalry Guards or the Siddi Risala were the imperial ceremonial guards of the Nizam, symbolically significant to the prestige of his princely state. Both communities lost their livelihood and normative privileges – if any – after the integration of the Hyderabad State into the newly formed Indian republic.

Colonial historiography has documented a considerable presence of Africans in the Red Sea region and many probably accompanied Hadramis to Hyderabad. As both are not endogamous groups, there has also been a history of marriages between them. There are instances of Siddi women from A C Guards getting married to and living in various Chaush neighbourhoods in the Old City such as King Kothi, Shalibanda, Humayun Nagar, Salala, Shaheen Nagar and Chandrayangutta.

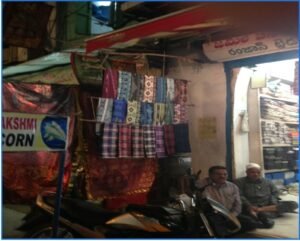

Further, similar to the Hyderabadi Hadrami diaspora, Siddis wear Ikat pattern sarungs or wrap arounds also referred to as lungi – the cloth for these are produced in the power looms of Indonesia and sourced through retailers in Dubai and Saudi – on banyans and short or long kurtas. Both communities follow Arabic naming patterns, where the first name is followed by bin (son of) for men and bint (daughter of) for women, which in turn is followed by the first name of the father. Siddis in Hyderabad are a patrilineal community. Also, Arabic was a language that both Siddi and Hadrami communities used in the past. Today, Deccani Urdu is the lingua franca of the community and only those Siddis (and Hadramis), a considerable number, who work or have worked in different Gulf countries may speak Arabic.

Sarung and cloth shop in Laad Bazaar, Hyderabad. Photo Courtesy: Khatija Khader

Chaush man in a Sarung, a busy street in Barkas Hyderabad. Barkas (a colloquial twist on the word ‘barracks’) and Chandrayangutta have predominantly Hadrami Chaush neighbourhoods. Photo Courtesy: Khatija Khader

In addition to these similarities, both Siddis and Hadramis play the Marfa and the Daff drums, making these musical instruments both Arab and African at the same time. These drums and the technique of playing these differ from the drums that Siddis play in other parts of India. Hyderabadi Daff drums are held at a tilt, as it hangs from a support around their neck, and the musician plays the skin on both the sides of the Daff. Earlier earthen pots called ghadas were also played, however, these have been replaced by steel pots today. Marfa drums are small circular drums held in the palm of one’s hand (these are smaller than the Daff drum), while the skin is beaten with a stick held in the other hand.

In the rainy season, the skin retains moisture and therefore, is usually heated before performances to produce a louder sound. Both the Siddi and the Hadrami compete for the same market, selling their music as an authentic marker of their community and hence the ownership of this art is closely tied to questions around livelihood. In Hyderabad, Marfa Bands usually perform at multiple venues, including, political events and religious or marriage ceremonies of all communities.

The Siddis of A.C. Guard practise in preparation for playing at a political rally, in Hyderabad (https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/301118/marfa-drumbeats-raise-the-tempo-at-poll-rallies.html)

Another site of similarity and contestation is wrestling. Both the groups have a tradition of Pehalwani, or wrestling. Siddi and Hadrami Pehalwan regularly participate in the Andhra Kesari wrestling competition. A popular example of Pehalwani is the sketch of Hamd Bin Abdullah Pehalwan (Siddi) on the packaging of Zinda Tilismath, a local over-the-counter miracle medicine manufactured at Karkhana Zinda Tilismath in Amberpet.

This essay is aimed to present to the reader how diasporas in the Indian Ocean have defined themselves through hybrid frames of assimilation and integration that problematises current discourses on multiculturalism, which privilege territorially bound notions of identity/culture and authenticity. While migration continued to shape the contemporary in Hyderabad with widespread migration to the Gulf since 1970s and to other parts of the world since 1990s, it is important to document the lost histories of communities, cultures and religions that are either ignored or oversimplified to accommodate a single linear national history. Hyderabad, and indeed the Deccan, remain embedded in the cosmopolitan Indian Ocean due to these historic connections.

[1] This essay draws on a recent article by the author in South Asian History and Culture. For more, refer to, Khatija Sana Khader (2020) Translocal notions of belonging and authenticity: understanding race amongst the Siddis of Gujarat and Hyderabad, South Asian History and Culture, 11:4, 433-448, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2020.1827598

[2] A popular Hyderabadi Riddle describing a Custard Apple. It translates as:

There is a green mosque, with white rooms

And in each room sit black mystics.

[3] http://zindatilismath.co.in/aboutus.html

References:

Campbell, G. “Slave Trade and the Indian Ocean World.” In India in Africa, Africa in India: Indian Ocean Cosmopolitans, edited by J. C. Hawley, 17–52. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Edroos, E., S. Ahmed, and L. R. Naik. Hyderabad of “The Seven Loaves”. Hyderabad: Sponsored by Sultan Ghalib Al Qu ‘aiti, 1994.

Harris, J. E. The African Presence in Asia: Consequences of the East African Slave Trade. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1971.

(The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. Content can be used with due credit to the author and to ‘Zariya: Women’s Alliance for Dignity and Equality’)

Dr. Khatija Sana Khader completed her PhD titled ‘Interrogating Identity: A study of Siddi and Hadrami Diaspora in Hyderabad City, India’ at the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Her PhD and publications explore the histories of migration of the Siddi and the seafaring Hadrami diaspora in the Western India Ocean and engage with concepts like diaspora, race and homeland/s in a non-western location. In the past Dr. Khader has worked/collaborated with various international and national organisations including Amnesty International, Arab League, New York Asian Women’s Centre, Centre for Equity Studies and OHCHR on Human Rights, Gender and Foreign Policy. She is currently teaching at the Centre for International Relations (CIR) at the Islamic University of Science and Technology, Jammu and Kashmir.

Email: kkhader@gmail.com